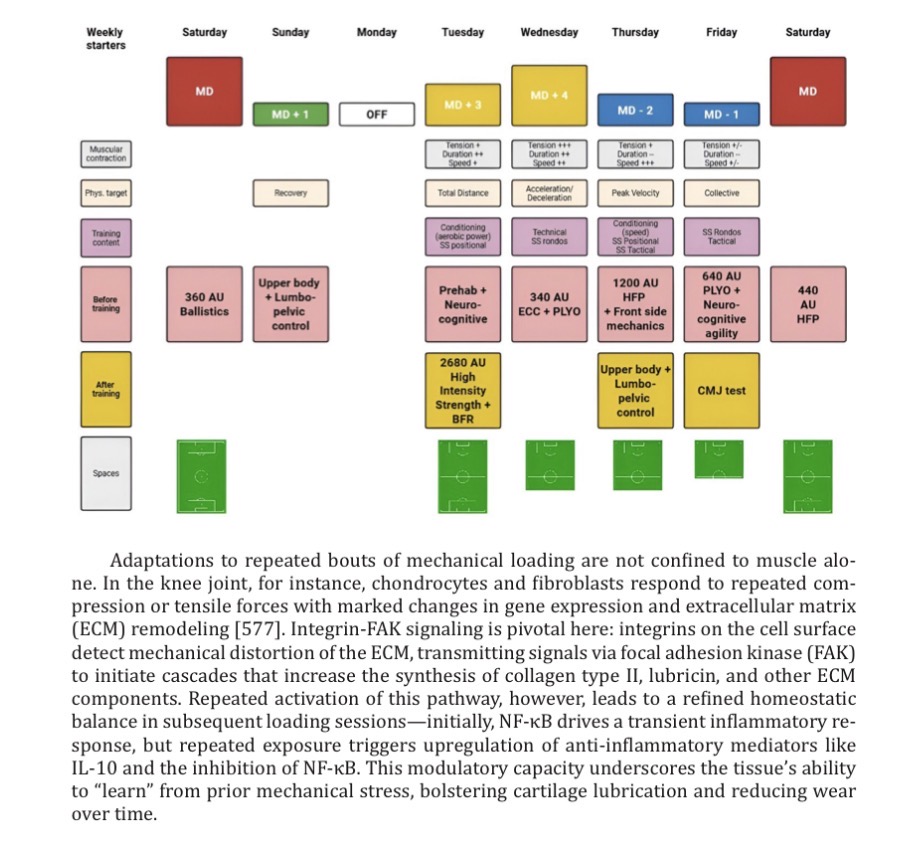

This progressive training series introduces four key exercises designed to strengthen the hamstrings in functional, sprint-specific contexts. Each exercise targets neuromuscular control, pelvic mechanics, posterior chain strength, and long-length loading—critical elements for both performance and injury reduction.

Exercise 1: Good Morning

To begin the series, we start with the Good Morning — a foundational hip-hinge movement ideal for developing hamstring strength at long muscle lengths.

Before progressing to more complex variations, this exercise lays the groundwork by providing three essential benefits:

✔️ Strengthening the hamstrings in a lengthened position: The eccentric, stretch-loaded nature of the good morning promotes adaptations that may increase fascicle length, improving the muscle’s ability to tolerate high forces and potentially reducing injury risk (Vigotsky 2015)

✔️ Building posterior chain strength and resilience: The movement effectively activates the hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors, creating a strong foundation for more advanced patterns (McAllister 2014, Jaeggi 2024)

✔️ Preparing the neuromuscular system: Ideal for building technical control, intermuscular coordination and hip-hinge strength for more complex, unilateral movements (Llurda-Almuzara 2021).

This makes the good morning not just a strength builder, but also a valuable tool in injury prevention strategies.

And this is just the first step. In the next phases of the series, we’ll explore progressions that challenge balance and neuromuscular control, and integrate pelvic control strategies — essential for improving running mechanics and overall performance.

Exercise 2: Single-Leg Romanian Deadlift

After establishing basic long-length strength and hinge mechanics, we progress to the Single-Leg RDL — one of the most researched and effective hamstring exercises.

Its value comes from how it integrates multiple sprint-relevant qualities, making it much more than a unilateral hinge.

✔️ Posterior Chain Power: The SL RDL activates the glutes more than many other hamstring drills — even surpassing high-speed running activation (Prince 2014; Van Hooren 2022).

✔️ Eccentric Hamstring Strength: It develops eccentric strength at long muscle lengths, with high activity in the biceps femoris and other key muscles (McAllister 2014; Van Hooren 2022).

✔️ Tendon Loading & MTJ Resilience: The RDL places substantial load on the tendinous tissue of the biceps femoris long head (Chen 2023). By enhancing elastic energy storage and release, it prepares the hamstrings for the extreme forces of sprinting — addressing a key injury risk: mismatches between stiff fascicles and compliant tendons at the muscle–tendon junction (Bayrak & Yilgor Huri 2018; Kim & Kim 2022; Huygaerts et al. 2021).

✔️ Pelvic Control for Sprinting: It challenges athletes to transition from anterior to posterior pelvic tilt under load — a crucial sprint mechanic that also reduces adductor strain (Sado 2017, 2019).

✔️ Balance & Stability with Overload: The single-leg stance develops sport-specific stability and proprioception, but instability often reduces prime mover activation. The Keiser ProSquat provides controlled stability, allowing athletes to maintain single-leg specificity while truly overloading the hamstrings.

⚡ The Single-Leg RDL is not just a hamstring exercise, but a bridge between hip-dominant strength, sprint mechanics, and injury resilience.

Exercise 3: SL RDL with Ankle–Foot Complex

Once the unilateral hinge is solid, we add a key element: intrinsic foot–ankle activation. Here, the toe presses down against a sideways pull from an elastic band.

🔑 Why? Because the ankle–foot complex is the base of movement. When engaged properly, it helps to:

✔️ Control foot posture and longitudinal arch stiffness (Kelly et al., 2014)

✔️ Control big-toe motion (Hashimoto & Sakuraba, 2014)

✔️ Improve arch function and propulsive force in running (Taddei et al., 2020)

✔️ Enhance balance, stability, and performance when integrated into training (Jaffri et al., 2023)

The foot–ankle complex isn’t passive. It stores and releases elastic energy, dictates how effectively force travels through the leg, and serves as the foundation of frontside running mechanics (McKeon et al., 2015).

Training hamstrings together with the foot–ankle system means we’re preparing the athlete for real movement mechanics, not isolated strength. We address the entire kinetic chain — from pelvic control down to the foot.

👉 As McKeon et al. (2015) highlighted, intrinsic foot muscles are often ignored in both training and rehab, with interventions focusing more on external support than training the muscles to function as they are designed. This exercise directly addresses that gap.

Exercise 4: Single-Leg RDL to Step-Up

With strength, balance, and foot control established, we now integrate sprint components. This variation enhances running mechanics and hamstring resilience at long muscle lengths.

🔑 Key evidence: Developing posterior pelvic tilt (PPT) control with gym-based eccentric exercises produces greater improvements in sprint kinematics than high-volume technique drills (Mendiguchia 2022; Alt 2021). This highlights the role of strength work that teaches dynamic pelvic control — not just cueing on the track.

Why this variation?

✔️ Mimics the 2-step sprint sequence (hinge → drive)

✔️ Demands explosive PPT, which generates large hip joint forces and drives efficient power transfer (Sado 2017, 2019)

⚠️ Without good pelvic control, athletes slip into excessive anterior pelvic tilt during sprinting, which over-lengthens the hamstrings and raises their tension (≈ ST +13%, SM +26%, BF +31.5%; Nakamura 2016) — increasing both demand and injury risk.

➡️ The goal isn’t just a strong hamstring — it’s a hamstring that delivers explosive power in the right sequence, and under the right control for maximal sprint efficiency and resilience.